It’s been 30 years since the Americans with Disabilities Act became law, but a powerful collection of oral histories shows the barriers in today’s world that still prevent disabled people from living their lives to the fullest.

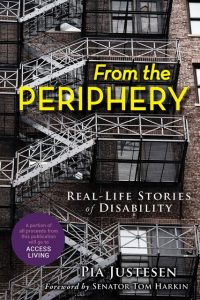

The author, Pia Justesen, is a human rights lawyer based in Copenhagen, Denmark, who focuses on minorities and people with disabilities. In 2014, she moved to Chicago and began working with Access Living, an organization that promotes independent living and equal rights for people with disabilities. There, what started as conversations with colleagues about their life experiences led her to gather the 40 first-person narratives from both activists and everyday people that make up From the Periphery: Real Life Stories of Disability.

Former Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), author of the ADA and one of its chief sponsors, wrote the foreword for the book of first-person accounts that vividly depict the lack of respect and inclusion that is a daily reality for people with disabilities. There are stories of children who are bullied in school for being different and face roadblocks to getting a proper education. Justesen also includes perspectives from disabled adults of all ages who encounter a dearth of employment opportunities and difficulties accessing public spaces, as well as challenge and heartbreak in navigating romantic relationships.

The stories shared are painful, raw, funny, honest and deeply personal. They give voice to what it feels like to live with the kind of social oppression and discrimination that can feel like “death by 1,000 paper cuts,” as the mother of teenage twin girls with autism describes. “You have to prove that you’re human,” says Mike Ervin, a grassroots disability rights activist who was born with spinal muscular dystrophy and uses a wheelchair. “You’re wasting all this time trying to prove that you’re human. Other people don’t have to do that.”

In a conversation from her cabin in northern Denmark, Justesen discussed what she learned from the project and shared what she hopes readers take away: laws are an important tool to combat inequality, but we need understanding, love and empathy to see real change.

This book really changed the way that I see the world and I’m curious what your goals were in writing it?

When I talk to people with disabilities, they always tell me that bias and preconceived ideas are the biggest impediments to genuine equality. I wanted these individual narratives to shed light on not only the diverse lives of people with disabilities, but even more so the barriers that the majority population put around people with disabilities.

Why was it important for you to choose a narrative structure for your book?

I think individual narratives are so powerful for understanding the real situation of a person. If you want to take a walk in those shoes of individuals with disabilities, you just need to hear more about their lives.

People with disabilities make up the largest minority in the world, but unlike race, ethnicity or gender, it’s not really acknowledged as a human rights issue.

People always talk about disability rights as something very special, and something that’s different from human rights. Disability rights are human rights. When we look at the situation in the U.S. and also in a wealthy country like Denmark, a lot of individuals with disabilities are denied their rights in practice and are not part of the labor market. Their right to privacy is being violated. Their right to protection of health and social security is being violated. People with disabilities might have special needs but they have human rights like everybody else that are really basic.

What do you think people most misunderstand about disability?

A: I think when people hear the word disability, they often think about a medical diagnosis or an illness. And I look at disability through a human rights lens. So I see disability as something that occurs. When there are barriers in your surroundings, the interaction between your individual impairment and those barriers is really what creates a disability. I think that’s really important to underline.

Anger is an emotion that people you included in the book frequently mentioned. Why did you feel it was so important to include that in the book?

A: A lot of people actually get angry. They argue that disability is not miserable. But not being regarded, not being respected, being constantly seen as less than, not being treated with dignity — all that is miserable. So these barriers in the world can make living with a disability a very miserable life. And that’s why some people with disabilities get angry and they fight to change the world. They fight to pull down those barriers so they can get genuinely equal opportunities just like everybody else. And I really didn’t want the reader to pity people with disabilities — that’s very, very important to me. I want the reader to respect people with disabilities.

How did you approach those conversations, given that you are not a person with a disability?

It was something that I thought a lot about because I am a white woman. I am privileged. I don’t have a disability myself and I was very concerned about my position doing this kind of work. I want my own children to grow up in a society where we respect diversity and are interested in and curious about each other in spite of all these differences that we have. So this worry, and my background in human rights work, convinced me that I did have knowledge and resources that I could use to help facilitate these narratives. My outsider position also made it possible for me to ask a lot of stupid questions, because there are a lot of things I didn’t know about as a foreigner coming from a very different society and from my very privileged position. For other outsiders to understand the barriers that we as the majority put around people with disabilities — often without knowing it — I think that was a useful position for me to have.

One of the disability rights activists that you interviewed talked about how she doesn’t want to accept what she called “a shrunken world.” In what ways does our world limit people with disabilities?

If you have a physical disability, there are a lot of physical barriers in the surroundings, but there are also structural barriers and attitudinal barriers. And if you have a developmental disability or a mental disability, the attitudinal barriers are even stronger. There’s one young man in the book who has a mental disability and he talks about the social oppression that he experiences. He has this period in his life when he’s in his early 20s and he calls it his “coming out.” He is trying to tell his friends and trying to talk to his family about this mental disability and nobody really wants to talk to him. They’re constantly deferring that conversation to another time or to another place. And that place and that time was just never there. So these attitudinal barriers and the stigma are really huge and obviously limit his life in a lot of ways, because there’s this big part of him that nobody really wants to see.

What is another example of the kind of social oppression people with disabilities face?

There’s a mother in the book who has three sons on the autism spectrum. Even though the other kids in school and the teachers are actually nice to her sons, they always eat by themselves at lunch. She finishes her story by saying, “Never let anybody eat alone at lunch.” And I think that’s something we can all relate to because not only is it a very lonely thing to eat by yourself, but it also sends a signal to everybody else that there must be something wrong with you because nobody wants to sit with you. You must not be likeable.

People on social media share a lot of stories about disabled people that are labeled “inspirational.” How does that framing strike the people you interviewed for the book?

There is a young woman in the book who is almost completely blind now and she loves going to the mall and doing what she calls a little bit of “retail therapy” when she’s in bad mood. She loves shopping and she loves trying on different clothes. When she talks about that, people always say, “Wow, you went to the mall by yourself? You’re so inspirational. How can you even do that?” And she’s like, “I do ordinary things. I don’t want to be admired for doing completely typical things that other people do all the time.” I hear that all the time. It sends the signal that the surroundings have very low expectations. You’re expected to just be sitting at home in the basement doing nothing because you’re blind.

What most needs to change in order for people with disabilities to be more fully included in society?

In the U.S. there are pretty strong legal regulations. We have the Americans with Disabilities Act, but there’s still a lack of implementation of the laws and there’s a desperate need of legal aid to be able to enforce the rules. But I also think that the attitudinal barriers, the lack of awareness and the lack of empathy and understanding is really a huge problem still. We can’t just work on the improved legal protection — we have to work on those attitudinal barriers as well.

The United States has yet to ratify the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with disabilities — what would that mean?

The U.S. is one of the very few countries that haven’t done so and it would be a very powerful signal to send to the rest of the world if the U.S. became a member. Right now, it’s probably not very likely, but I’m hoping that it will be again in the future because I think it would send a signal to other countries that disability rights are indeed important human rights.

What kind of feedback have you gotten about the book — both from the people who appear in the book and from readers?

For people who have been in the book, it’s been a bit tough to see their stories on paper, but they still believe in the importance of doing so. But I’m just truly grateful that they actually chose to share their stories. One of the bigger things that’s been very eye opening for many people without disabilities is to realize that disability is not just about medical diagnosis. It’s really about the barriers and the surroundings. And it’s one of the most important things that I would like to promote: disability is not about fixing the individual, it’s about fixing the environment, fixing the surroundings, pulling down those barriers. And for many people, that’s a new way of thinking. If more people would look at disability in that way, I think we would come a long, long way in promoting genuine equality.

How have the people you’ve met in the process of writing this book changed your life or your perspectives?

We are all just so much more alike than we’re different. We really have the same basic needs and wants. We all want a home that’s safe. We want to be able to be with our friends and family. We want to live a life in dignity. We want to be respected. We want to learn and go to school and have a job and be able to sustain ourselves and live independently. It’s really all the same basic needs and wants that we have. And that’s been one of the major lessons for me on a more emotional level, because it’s been what I’ve been preaching as a lawyer for all these years, because that’s what international human rights are really all about.

For more information:

http://www.piajustesen.com and https://www.facebook.com/storiesfromtheperiphery

See Jenny and Pia’s conversation here:

Editor’s Note: The editor of this blog has a family member whose story is shared in the book described above.